Production flexibility down to the single copy, fast turnaround time and cost savings

Production flexibility down to the single copy, fast turnaround time and cost savings. Digital is easy to say today, but there are three phases to the production process, and even pre-press and post-press must be part of a digital ecosystem that doesn’t interrupt the workflow. This is how post-printing – from finishing to bookbinding – is responding to the demand for personalization and becoming a strategic ally of time-to-market.

By Lorenzo Capitani | On PRINTlovers #85

The glittery Barbie, the embossed basketball and the ice that genuinely looked wet: it was 2012 when Scodix, during Drupa, was the first to show that digital enhancement was not only possible but was also ready to come out of the experimentation phase and put itself on the market as a valid alternative to traditional mechanical systems. That was a Drupa of technological buzz, it was the year of Landa’s nanotechnology and change was in the air, where the new watchword was “digital”.

The turning point

A lot has changed since 2012. The print market has undergone a profound transformation that has fostered the development of digital in all its phases. And while the transition from film to CTP was above all a question of technological evolution – which was due to the spread of the pdf and the progressive computerization of printers – digital printing was the right technique at the right time. The first economic crisis in 2008, the explosion of the internet, the collapse of print runs and finally social media and streaming, on the one hand, have shifted communication to virtual, reducing the demand for printed products. On the other hand, they have given a robust, innovative push towards efficiency. This has encouraged digital printing to develop, establish itself and respond in just a few years to the needs of a market that was no longer suitable for large formats and long print runs. Luddites who turned their noses up as they ran their fingers over the sheets coming out of the first Indigo, complaining that they looked waxed, had to reconsider when a study by the Rochester Institute of Technology showed that digital output was the most faithful to colour proofs. Now digital printing is a fully-fledged alternative: it no longer has a break-even point forced down to the bottom; it has come alongside offset and in many cases replaced it; it is no longer just for advance copies, personal printing, very short runs, sampling or variable-data guerrilla marketing experiments by some Coca-Cola advertising visionary.

Digitizing the finishing

But there are three production phases, and after printing, the real challenge for digital is the post, from finishing to bookbinding. And it’s not just about making the machines intelligent, increasing electronics or connecting them, of course. It is also and above all about minimizing the analogue part of the process to achieve the same KPIs as digital printing: no matrix costs; no start-up; constant quality production throughout the print run; immediate job changes and zero waste; production flexibility down to the single copy. Frank Romano’s intuition over a decade ago proved to be spot on. “At present (in 2008) more than half of all print jobs in the world have a print run of fewer than 2,000 copies, and by 2020 even one in five will be printed in just one (or uniquely), given the growing trend towards print-on-demand.”

Personalized printing today is no longer an experiment to explore new marketing avenues, but a real structural approach; it is a deep involvement that, from the digital engagement we experience online every day, has invaded the real world. If Google “calls me by my name”, today I expect everything to do so. It has been proven that personalization can produce 31% more profit than generic marketing materials. And here what comes into play is enhancement, that wow effect estimated to push the buyer into paying an additional price of at least 24%. Or even more, if the piece is unique.

But how has the finishing managed to become digital and close the gap with the other phases that precede it? First of all, by trying to create integrated systems that cover the end-to-end process and create machines that keep as many jobs as possible within the same printing company, touching the sheet as little as possible. Then, by computerizing the machines as much as possible. They are now driven by sophisticated software that directly acquires the work and runs it without passing through dies or intermediate substrates: no dies, no frames, no clichés. It’s a machine-software dialogue guaranteed by highly precise control systems. Vacuum tables, cameras, barcode and notch readers, lasers and photocells monitor sheet after sheet, guarantee the register and continuously adapt to any changes. At this point, the numerical control, or rather digital control, opens up to variable data and non-stop job changes, without any start-ups, and to copy by copy personalization. This is also the basis for technological research that is extremely responsive to market and customer requirements.

Varnishing, laminating and die-cutting: these are the areas of post-press that have benefited from this technological push and have enabled commercial outlets beyond web-to-print, making digital packaging, or what is now called web-to-pack, possible. There are small formats or few copies – the DNA of digital – but also large formats and high print runs, the terrain of traditional analogue technologies. This is the case with Highcon or Sei Laser who, with their digital machines, are competing with conventional die-cutting machines.

Digital Varnish

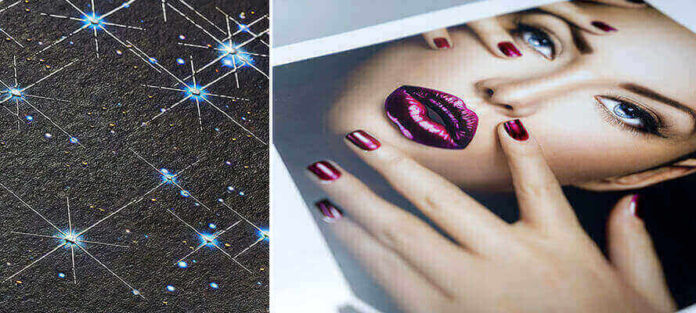

Varnishing was the first enhancement to switch to digital and perhaps, beyond the operating methods, remains the most surprising technique because it has succeeded in combining the effects of screen printing, UV coating, embossing and hot stamping.

Konica Minolta’s MGI JETvarnish 3D solution allows spot coating, also in combination with foil application, with 2D/3D effects in thicknesses ranging from 21 to 116 microns in a single pass on digitally printed sheets, but also traditional offset. The drying and curing of the coating are carried out using ecological ozone-free LED technology and the reading of the sheets for the register is done without reading the print marks but directly from the graphics scanner. This makes it an extremely versatile technology that can also cover B2 to B1 formats and is suitable for all types of print runs, from prototyping to large volumes.

The Scodix machines, from their very first appearance, have made processes accessible that would otherwise be complex and constrained by runs, frames, clichés and start-ups. They not only varnish in register, but in Braille mode they reach thicknesses of up to 250 microns, i.e. 100 times more than traditional spot coatings, and up to 1 mm in Crystal mode, taking advantage of four machine passes achieved with the utmost precision thanks to absolute register control. But other lamination effects are also possible: applying a metallic colour to the polymer (such as Scodix 351, distributed by Luxoro) even on matte papers or hand use; glittered while maintaining the tactile sensation of classic processing; or holographic through micro-engraved Cast&Cure films.

All this is possible thanks to the digital data that is instantly converted into graphics, to the printing that has almost perfect and constant precision, and above all thanks to the polymers and the machines’ ability to calibrate their drying speed – immediate for high thickness and fine lines, slower for large surfaces or reduced thicknesses. But digital means not only aesthetic effect and process control but also variable data or finishing, which is unthinkable with UV coating or classic frame screen printing. Another interesting synergy is the one between Kurz and HP: the Kurz DM-Jetliner is a digital printing unit integrated with the HP Indigo, which simplifies into a single pass the production process for printed products with metallic effects. The main feature of finishing with DM-Liner is the possibility of problem-free multi-colour overprinting thanks to the smooth and homogeneous metallization, not only on paper but also on PET and PP.

Sleeking

Another technique – sleeking – takes full advantage of digital printing, and it consists of transferring a film on the toner directly onto digitally printed sheets of paper. In this case, it is not really a digital finishing, but an analogue processing integrated with digital printing. Sleeking is like a film on which a polymer is coated and once applied, it appears glossy like a lacquer or matte, with an orographic or metallic finish. The particular material that makes up the film is coated on a transparent liner, which is removed once the process is completed. The sleeking is chemically combined with the toner used by digital printers and the contact with the hot rollers allows the finishing to be transferred onto the printed portions of the sheet. It’s better if it’s in black for coloured foils: on areas without toner, there will be no effect, and the film will remain deposited on the liner. In addition to spot application, this process allows exciting results to be obtained by using a double printing pass: for example, a part of the image is printed and laminated, the sheet is put back into the machine to print the remaining portion of the image and the application of sleeking. But it’s also possible to overprint the metal foil in four-colour with a process similar to cold foil: first, the part to be enhanced with the sleeking is printed, the foil is applied, and then the rest of the graphic is returned to the machine to be printed. (FoilPress_blingPrint_Melb.jpg, gold-foil.jpg, sleeking-step-by-step.jpg) The link doesn’t seem correct

Speaking of colours and effects, the possibilities are enormous. Magdata, for example, offers two ranges of products. The Digital Foiler allows the transfer on toner with reserve white or metallic films in gold, silver, red, blue, green, pink, purple, bronze colours and even with a hologram and iridescent effect, or to apply a transparent film to polish in register without passing through traditional lamination or UV coating. The foils are suitable for sheets printed on Konica Minolta, Xerox, Indigo and Canon digital presses. Added to this is the polypropylene film series specifically for digital printing for products requiring die-cutting, creasing and folding. Here they range from classic gloss or matte to velvet and soft-touch effects in the Temptation and Velour series.

Made to measure creases and cuts

The area of post-press that has really managed to bridge the gap with analogue and become digital is die-cutting for both cutting and creasing. Esko’s cutting tables were undoubtedly the driving force behind this, and they also applied the plotter technology to the post-press stages. Today, these tables have a very high level of automation and integration with digital printers, unwinding and winding reel systems; they change job in the same work cycle, adapting cutters and blades according to requirements, process a variety of materials other than paper and cardboard and are suitable not only for the packaging for which they were created but also for displays, labels and flexible packaging. (Esko kongsberg-c-heroshot.jpg)

Zund’s offering also goes in this direction, proposing digital solutions in which, in addition to cutting technology, the strong points are a database of jobs already produced, to make it easy to reproduce runs already completed to “put back in the machine”, and software capable of guiding the best positioning so as to reduce waste and scraps to a minimum. It is the world of plotters and small format that has benefited from this digital transformation. On the one hand, printing plotters, not just flatbeds, have been equipped with blades for the simplest cuts; on the other, digital die-cutting machines have emerged that have also spread this technology to the smallest printers, digital natives or the most reluctant. These machines – sheet-fed 35×50 or 50×70, or even very narrow-band reel-to-reel – cut, perforate, carry out half-cuts, have automatic loaders and integrate in line with the digital printers. Above all though, they don’t need dies and can change the type of cut at each pass: in no time at all a die-cut case can be obtained, because the machine cuts and creases where it is needed. This is the case with small formats for limited but precise and very versatile runs.

An excellent example is Motioncutter by Konica Minolta, a system suitable for formats from A4 to 53 x 75 cm, expandable up to 100 cm. The system allows a wide range of highly creative applications, achieved through the use of a unique technology: the shapes are cut by a moving mirror laser that follows the sheet along the paper path. This makes various jobs possible, from cutting to half-cutting, and then engraving, creasing, perforation and the patented Namecut for cutting out a name, logo or any other personalized data imported from a CSV or QR file. The production of labels and printed material using variable data on a wide range of substrates is particularly effective.

In the large format field, digital creasing and die-cutting have also made great strides: you just need to see a Highcon machine running. In the case of creasing, for example, once the job has been acquired from a file, the machine “writes” the creases on a plate with a liquid polymer that is then cured with a UV lamp. (Highcon digital cordon.png) The sheet passes between the cylinder with the digital creases and a pressure cylinder and is detected exactly according to the set path. Cutting and half-cutting are performed by laser, which also allows perforation and writing, since the substrate can be engraved by ablation, also as an anti-counterfeiting system. Although they are on the same line, creasing and die-cutting are separate steps that can be managed independently of each other, so each piece can be processed and customized as a unique piece. Everything is promptly checked by sensors and photocells that guide and check the work.

An example is the Christmas card produced in 44,000 different variations by Iggesund Paperboard in association with Highcon. (Christmas card00306.jpg)

We’re talking about machines that produce from 3000 to 5000 copies per hour, in the bigger versions, and which allow thicknesses from 200 microns to 2 mm and the personalization of each product, with a considerable reduction in processing times because start-ups are effectively eliminated. But one of the most significant advantages is the complete absence of the die-cutter, which means not only cost and production time but also the absence of storage and environmental protection.

Similar solutions have been developed by SEI Laser, which has chosen to have a system of male-female clichés in storage with polymer extrusion, a bit like a 3D printer. This makes it possible to process not only paper and cardboard but also materials such as polyester and polypropylene, 1.5-2 mm microwave cardboard and thermo-transfer. If the word “laser” brings up the idea of burns, any doubt is removed by Ettore Colico, Converting Director of SEI Laser. “To avoid burns the laser must be the right one, as thin as possible, and its energy must be concentrated in a point that is as infinitesimal as possible: this allows clean cuts without any yellowing. In addition, it’s essential to remove fumes from the air which, if not properly removed, will dirty the paper. To eliminate the effect, the paper is cut with the print facing downwards so that the lasering remains inside the box.”

Digital packaging

Digital die-cutting and creasing pave the way for digital packaging: unique pieces, short runs with no minimum production sizes, samples or prototypes to surprise the market but also to explore new solutions. No start-up costs, no equipment, no matrix and die-cutter and a minimized time to market that also translates into very little stock, with the peace of mind of ordering what you need when you need it. This is also the philosophy of web-to-pack, web-to-print’s alter ego in packaging version. Portals such as pack.ly or zooxbox.com allow the creation of boxes, cases and displays starting off from a rich library of stock designs, personalizable in size and graphics and suitable for different types of products. For each type of pack, you can also define the materials and download the die-cut stock design on which to mount your graphics. Once the project has been reloaded in pdf, with the levels of the die-cutter and graphics, it is possible to visualize the yield in 3D before deciding on the type of printing, finishing (varnish or foil), quantity of pieces and shipping.

To do this, the entire process, from printing to die-cutting, must be digital. Packaging is a growing market: one quarter of all printed products in the world is packaging. Shorter print runs, shorter delivery times, customization, and finishing are the main conditions thanks to which this sector is growing by at least 3.3% per year. Web-to-pack is one of the roads for digital packaging, but it’s not the only one: it obviously offers a limited choice of formats, special colours and finishing because its strength is standardization so as to provide speed and competitive costs; it’s equally true that print shops respond to customers’ requests by expanding the range of offers. The customer configures their product online and can upload their images, while the print shop receives a standardized order that is produced quickly and at competitive costs. But now that the entire process is covered, digital is also investing in packaging production sectors that deal with large volumes, such as labels that integrate with the packaging, and that have realized that digital can be used to incorporate long print runs in flexo or offset, primarily because of the infinite possibilities for personalization and customization. (Laser_Cutted_Paper_Personalisation_3.jpg and packaging-personalised-packly-playcopy.jpg)

Smart bindings

Book printing is a sector in which digital has had a significant impact in terms of web-to-print: many publishers have reactivated historical catalogues, have thrown themselves into self-publishing in the wake of Amazon or Google, or have had to turn to digital when print runs don’t allow traditional printing: the days of the Cameron belt press are a distant memory. And this is why so many book printers have combined offset with digital printing – not just for colour and no longer only black volumes – and digital in-line or near-line packaging systems. For a low-demand long seller, it’s better to print when you need it, rather than having copies in stock. All the manufacturers of bookbinding lines – from Muller Martini to Smyth, Tecnau to Plockmatic and Meccanotecnica from Bergamo – have developed digital solutions, i.e. highly technological, computerized and ductile solutions; they take advantage of the ability to change jobs, formats and hot run sheets directly to make even single copies possible. Apart from reel-to-reel systems that come out divided into signatures, digital machines typically come out in sheet-fed format, which makes it more delicate to collect and transport the block. To make these steps easier, either pre-glueing, which holds the book block together before it goes into paperback, or stacking, by collating the sheets from the accepted input formats to the final output formats. The glues have also been adjusted, because standard hotmelts sometimes reject toner, establishing the use of PUR adhesives in bookbinding. There are no significant limits in the packaging: milled and stitched paperbacks are made without any problems from stale sheets and signatures, whether four or eight-page, or from reels.

Workflow and print 4.0

As we’ve seen, digital means increasingly automated machines for increasingly unique products. But it also means experimentation, extreme customization, speed of execution and therefore the ability to reduce the time between the creative idea and the product’s release on the market. To do this, a highly technological Industry 4.0 production approach is essential, in which the machines dialogue with each other and the entire process is digital. Any interruptions in the digital chain are bottlenecks that not only slow things down but also translate into costs. If the path indicated by the market is mass customization – i.e. producing goods precisely as the individual consumer wants them, but with the time and costs of mass production – technology isn’t enough. A change of mentality is needed that revolutionizes the production processes of printed matter, from creativity to delivery to the customer. This has a direct impact on profit margins and is reflected in the customer always looking for the best price in the shortest time, without sacrificing quality and service. A digital machine today, for example, has a much lower learning curve than a traditional technology. In a study by Jim Kehring, coordinator of the strategic partners at AB Graphic International, a printing and finishing company that has been on the market for over 60 years with more than 11,000 installations, it says: “In the world of conventional finishing, it takes a lot of time and money to make an operator profitable. With digital, it takes on average six weeks to make an operator ready and profitable: if they can use an iPad, they can probably run the press.” Hence the attention of machine manufacturers to the software that controls them, but also that pilots and interconnects them, not only for digital natives but also for giants like Heidelberg who developed Prinect Workflow. The Italian company B+B International, for example, has created Packway, an ERP for highly digital graphics companies, integrated with Esko software. The construction of an ecosystem in which machines, software, operators, files and printouts easily interact today is based on standards such as PDF and JDF/JMF, such as XML, XMP and SQL queries, cloud computing and remote working, but also on the possibility of following the preparation, design and production phases and, within it, activating the processes needed when they’re needed without any downtime. This means that reading the barcode or QRs on the sheet to call up the job to be done is as essential as the print marks. (Esko i-cut automator.jpg)

A virtuous relay race

But will digital finishing replace traditional finishing methods? Perhaps the Drupa 2020 that Covid wiped out would have given us an answer: this edition was set to consolidate these technologies and integrate machines to cover the entire process end-to-end. Let’s try to hypothesize an answer anyway. In reality, as always, the truth lies in the middle, and the choice depends on the type of print and its destination because there are undoubted advantages in the potential of digital and because large volumes will always be a cost problem. The right driver is always the best price for the same quality. But in all this one thing is sure: the digitization of the process, beyond the digitization of the jobs, is a must for innovation. For the first time, analogue and digital are not necessarily in competition, but they are an invaluable tool in the hands of creative people. It’s only a matter of exploring.