Music to touch

Once upon a time, there was shellac. And then vinyl, magnetic tape, CDs, with sleeves, cardboard covers, digipaks to stack, booklets to browse, read and look at. Until the beginning of the 21st century, listening to recorded music meant having an experience that involved all the senses, involving the emotion of waiting, buying at the point of sale, physically storing the media. This was so much the case that the love story between music, design and printing is one of the most passionate ever. But today, when music is mainly dematerialized, can you still "collect beauty"?

By Michela Pibiri | On PRINTlovers #85

Almost forty years have passed - it was August 1, 1981 - since MTV started its broadcasts in the USA with the video of the song "Video killed the radio star", first released by the Buggles in '79, which was to become the synth-pop icon of the '80s. The choice of the first television network entirely dedicated to music was an important milestone, steeping it - highly ironically - in that nostalgic feeling that comes back every time new technology seems to want to sweep away the past which we are used to and fond of. In hindsight, we know that the radio has not only survived TV and the music video boom, diversifying and redirecting its media power and social role. But it has also become, in the 2000s, an inextricable part of the Internet, regaining its ancient role as an influencer of the public's tastes and opinions. After the music video on TV, the second substantial revolution in the music industry took place with the birth of the first mass peer-to-peer service, Napster. Since the early 2000s, it has eroded the revenues of physically distributed music, thanks to a massive spread of piracy later curbed by the regulation of paid downloads. This took place with the arrival, in 2005, of streaming services such as Apple Music, Spotify, Deezer, Amazon Music, and YouTube Music, to mention just some of the best known. Their weight gradually increased until 2015 and has grown exponentially over the last five years to raise the fortunes of a global industry that experienced its darkest years between 2010 and 2015.

Past, present and future of physical music

According to data provided by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI), in 2001, global receipts from recorded music were almost exclusively from physical distribution (98%), with a minimal percentage (2%) coming from public performance rights for recordings. Eighteen years later, in 2019, the revenue breakdown has been wholly revolutionized: physical accounts for just 21.6% of revenue for a total of $4.4 billion. 56%, or $11.4 billion, is from streaming services; the remaining slice is divided between performance rights (12.6%), downloads (7.2%) and synchronization, i.e. revenue from the use of music for commercials, soundtracks and video games (2.4%).

In Italy, the data provided by FIMI - Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana - outline a similar picture. In 2019, physical accounted for 22% of the industry's revenues, amounting to approximately €53.4 million out of a total of €247.8 million. Of this, €37.25 million came from the sale of CDs, €14.7 million from the sale of vinyl and €1.5 million from "other physical", a category that includes magnetic media such as old music cassettes and digital media, such as USBs, mainly intended for special and promotional editions. The majority of revenue, in 2019, came unequivocally from the digital segment (71%) primarily consisting of streaming and, to a residual extent, downloads. In September 2020, FIMI published the first data influenced by the effects of Covid-19: during the lockdown the sector was, predictably, driven by digital, accounting for 86% of all revenues, with 82% from streaming, which saw an increase of +33% in subscriptions in the first six months of the year. The temporary closure of physical shops and the blocking of record shipments by Amazon marked a dizzying collapse in the physical sector: CD sales halved (-51.44%) compared to the first half of 2019. The vinyl niche, on the other hand, held on to its position, covering 5% of the market. However, the overall balance sheet for the industry is positive: the entire Italian record market grew by 2.1% compared to 2019, and this result is partly the result of the 18app "culture bonus" that generated a turnover of €10 million (August 2020) with the involvement of 390,000 young people who took part in the scheme. Even disregarding the health emergency, it is therefore clear that the trend towards dematerialization leaves no room for a turnaround. However, even though it is in the minority, the physical continues to be the second-largest source of revenue in the global recorded music industry, and - according to Billboard music magazine - will remain so, possibly even growing in the coming years. This is because of the artists' fanbases, who will still go to shops to grab the latest releases – even if it's difficult, now, to imagine crowds gathering to wait for an autographed copy - and a growing number of collectors, especially vinyl lovers.

Collecting beauty

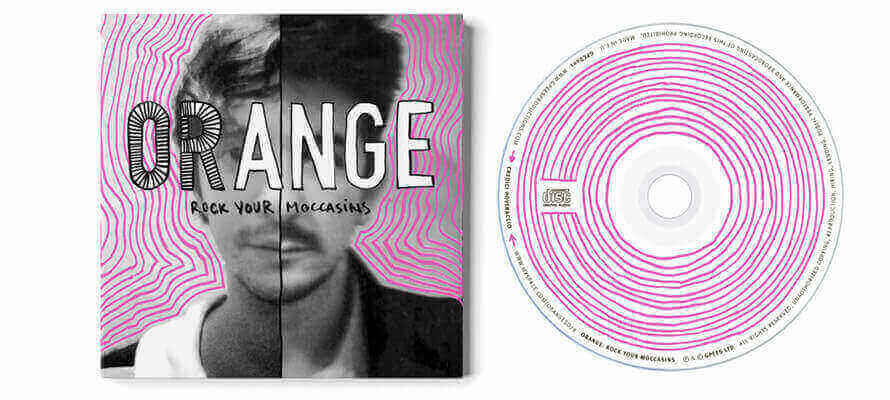

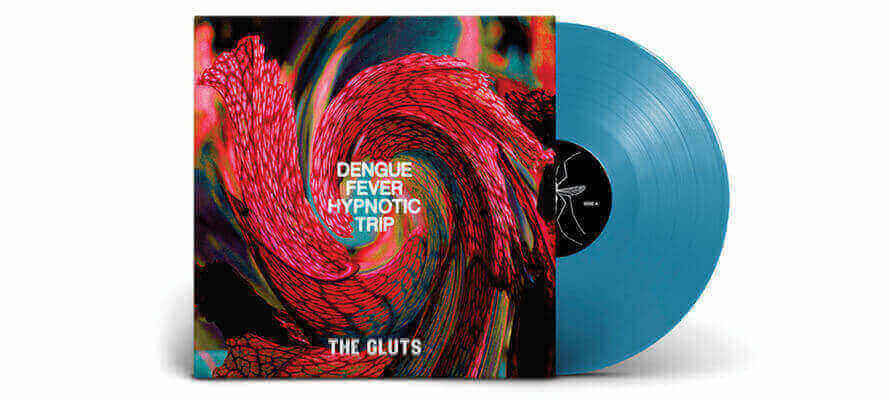

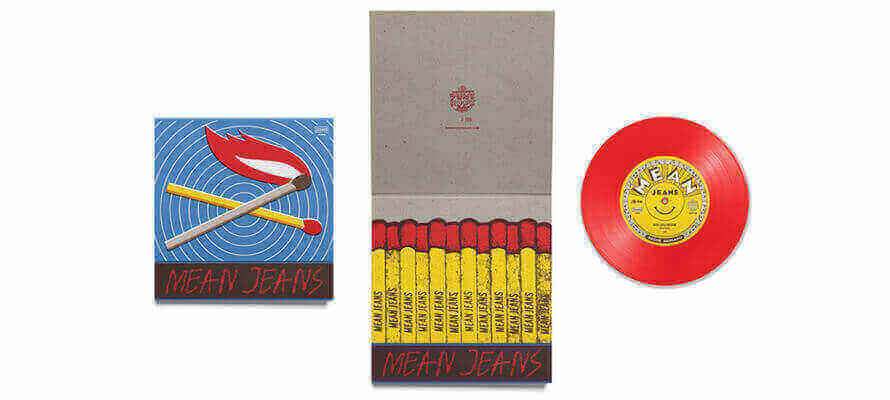

In the face of a smaller quantity of printed discs, which is also the result of a cost reduction policy, labels are beginning to focus on the quality of the editions, which not only has greater appeal to an incredibly demanding audience but also justifies higher sales prices. From this standpoint, limited editions, anthology and experiential sets play an essential role, with the production of printed objects. These range from boxes - often enhanced - to vinyl sleeves, from digipaks of CDs with their accompanying booklets to books and photo albums, posters, silkscreen prints and collector's cards, decorated gifts, t-shirts and other printed textiles, to numerous collectable memorabilia such as faithful reproductions of concert tickets, passes, photographs and manuscripts. Real memorabilia, in short, capable of creating or strengthening the emotional bond between the public and artists, but also exclusive objects - because they are expensive and limited - set to gain value over time.

There is no doubt that the relationship between graphics and music is one of the most compelling love stories of the 20th century. The birth of the 33 rpm LP, introduced in 1948 by Columbia Records to replace 78 rpm records - much smaller - in shellac, gave the creativity of graphic designers, illustrators and photographers ample expressive space in terms of the covers' printable surface, leading to collaborations between music and visual arts that have had a massive impact on the collective imagination. Just think how strong the echo still is of "Unknown Pleasures", Joy Division's first album. Its artwork, created by Peter Saville in 1979, was inspired by the frequency graph of the first-ever observed pulsar published in the Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Astronomy. Today it is now used in fields ranging from fashion to internet memes, from home decor to body art. Buying a record because of its design is, in the words of another giant in the industry, designer and printer Stefan Sagmeister, "collecting beauty". It's a pleasure and a psychological need well described by Keele University's 2019 study, The environmental impact of music: digital, records, CDs analyzed. "In a world where more and more of our economy and social relations take place online, records and other "vintage" formats counter this trend. The revival of records reveals what we want to see on a broader level in our world: experiences that retain their value and that last over time, thanks to our loving care. Older music formats have a sense of importance and permanence, they belong to us in a way that our virtual purchases simply don't."

The environmental cost of music

We could easily be led to thinking that the advent of streaming solves the problem of the environmental impact of music. In fact, the media used in the music industry - apart from packaging, which tends to prefer recyclable paper and cardboard instead of fragile, non-recyclable jewel cases - are anything but ecological. While the shellac used until the early 1950s to produce gramophone records was a natural thermoplastic, the market was later conquered by PVC (polyvinyl chloride) and the inseparable combination of polycarbonate and aluminium in CDs: fossil-derived materials that are not only not recyclable, but take centuries to break down. The Keele University study mentioned in the previous paragraph, however, dispels the myth of dematerialization without environmental costs: considering that electronic files are stored in servers that are always active and refrigerated and that their transmission on our personal devices involves constant use of energy, the answer as to what is more sustainable between digital music and physical music is by no means obvious. Much depends on individual listening habits, concludes the study. "If you only listen to a track a couple of times, streaming is the best option. If you listen to it repeatedly, a physical copy is best; streaming an album on the Internet more than 27 times will probably use more energy than it takes to produce the same CD." Of course, the energy cost of playing a physical disc in HI-FI is also calculated, which is one-third of the energy needed to play a streaming track in HI-FI. Finally, there are two options suggested for reducing your impact while listening to music: in physical music, buy vintage vinyl; in digital music, prefer downloading to streaming and keep the files to listen to over and over again locally.

Welcome to record clubs

In the prolific world of subscription boxes, music has also carved out a space for itself, bringing the concept of subscription back not only to streaming services but also to the material and collecting dimension of music. The phenomenon has gained a foothold among fans of analogue media, especially in the USA and UK. There are formulas ranging from a simple monthly selection of LPs, chosen according to the preferred genre as in the case of Vinyl Record Club and VNYL (which makes a selection based on the music preferences expressed on Spotify), to themed boxes – like MoshBoxx – that in addition to vinyl and CDs also contain stickers, t-shirts and other gadgets, up to boxes that offer only accessories to collect or use for festivals, concerts and raves. In this context, the American publication Vinyl Moon, founded by blogger Brandon Bogajewicz, stands out because of its creativity. It's a monthly based on the search for new music ranging from indie rock to electronics, which is selected to make a mixtape, then cut on vinyl and supplied with deluxe packaging with original graphics and booklets, and all shipped in a custom corrugated cardboard box. Physical, very physical - but not over the top: Vinyl Moon, for example, also has its own channel on Spotify.

Music on the brain

On the far pole of dematerialization we find the future applications of Neuralink, the neuro-engineering company founded by Elon Musk, whose research aims to integrate into the brain technologies capable of overcoming or attenuating various forms of neurological disabilities. Neuralink is developing devices that can be surgically implanted and that can be remotely controlled, and does not exclude that, in parallel with medical applications, solutions can be developed that enable, for example, listening to music without the use of external devices. Given the technical difficulties to overcome, however, this still seems far off and certainly not within everyone's reach: it's best not to get rid of your speakers, headphones and turntables for the time being.

---

INTERVIEW

Paolo Proserpio Luxury, skateboarding and independent music

In an increasingly dematerialized dimension, the physical can have a future as long as it becomes an added value compared to digital content. We talked about this with Paolo Proserpio, a designer who began his career in Gucci's graphic design studio - it was the Tom Ford era - and who has worked with Versace, among others, for many years. An expert in screen printing, he loves to "build and trade" by designing products that are printed: among them, many records for independent artists and labels.

Music is increasingly dematerialized. Is the physical medium destined to disappear or, on the contrary, can it reinvent itself, communicate something different from the past, and become a vehicle for innovation?

Like everything that's free or easy to find, when it's completely dematerialized music also loses value. In terms of perception, it's crucial to find physicality, especially when it's a rare edition or one that needs long waiting times. Collectors buy records both because they like the design of the object and because the digital covers don't contain all the information that the physical object offers: who recorded it, who played what, who did the graphics, or even simply the acknowledgements. This is information that artists may put on the site or on social networks, but it's completely missing on streaming platforms. Having a record in your hands is like buying a book and reading it from start to finish - it offers an experience that has many dimensions: the cover, the back, the booklet, the photos, the gesture of taking off the vinyl, and last but not least the material, which communicates more... of course I don't deny the advantages and practicality of digital music in everyday life, but personally, as a designer, I've had an increase in requests for physicality, because independent artists especially have realized that the object to sell is more useful than ever.

How important is it to focus on design and the aesthetic and sensory quality of the printed product, and what are the main trends at the moment?

In current record production, there are two basic schools of thought. The first is the one tied to large volumes, which require standard classic formats - such as digipak for example - so they allow large scale cost reduction. Not only that: the classic format is often a choice that meets the tastes of the public, who aren't always ready to receive something different than usual. The second concerns short runs: a philosophy mainly linked to independent labels who decide to focus on refinement and originality to boost sales. Unusual packaging makes headlines and is designed with the idea that the object makes people talk about it.

If we talk about versioning and personalization, one of the main trends at the moment is undoubtedly coloured vinyl, with the diversification of colours representing a form of personalization. For sure the idea of owning an item in a limited edition or in different covers to choose from is attractive for collectors and completists, who can buy all the available versions. And then there are the numbered editions that make the item unique: all made possible by digital printing. Some forms of customization can be done by hand, as long as you think about short runs and stay in an almost artisan dimension: I often work in this way. Bizarre formats, which come out of the ordinary, are an excellent incentive for collectors, even if they have some archiving problems. But they do tend to be objects often made to be exhibited.

You have carried out many projects in the field of music. How far can experimentation go in terms of customization and production of objects other than standard ones?

If there are a lot of challenges to be met in working with the majors, in the independent world - where the production runs and costs are different - you can give space to extreme experimentation and craftsmanship, without having to worry about the machinability of the projects. This is the case of several projects I've carried out: with the punk-rock group Pay, for example, we wondered about the raison d'être of the CD, which nobody listens to anymore, not even in the car. So, in designing the 2016 album "Canzoni per gente che non si fa più" ("Songs for people who don't make them anymore") we decided to cut all the CDs in half with a saw, one by one. Clearly, the inaccuracy of the cut created the uniqueness of the record and a lot of interest from the public. However, so as not to make the album totally unlistenable, we hid a smaller bag inside the package, which contains the whole CD and which you only discover after your initial astonishment. The covers are all different too: I printed them with a photocopier on fluorescent paper in A3 format, then they were hand-folded. I glued the lyrics on the photocopier and "photocopied" live the faces of the singer and bassist: each print has a different image than the previous one. For the band Aurelia 520, (ed. 's note: also the name of a printing press) I created a project with about 500 Polaroids that I personally shot on the theme of music: each CD copy has a different original Polaroid.

What relationship do younger people have with the physical?

If I have to think of a representative - but not complete - sample of the new generations, my students tend to be single-issue: at the moment the most widespread way of communicating in music is trap, a genre that started at the same time as digital. A lot of artists, especially the more niche ones, don't even come out on physical, and my students rarely buy special or limited editions of an album, even if it may happen that someone still chooses the physical because of the graphics. Compared to previous generations, students invest their money in other things, especially clothing or accessories, to show their niche that they exist: wearing a T-shirt, taking a photo and posting it on Instagram. For obvious reasons, the habit of buying a record, the ritual of hunting it out, the sense of expectation created by reviews... a purely generational ritual that ends up on Instagram in the same way: 40-year-olds buy vintage records on Discogs or in street markets and post a photo to share the experience of the past.

What mixes can we find between music and luxury packaging?

Music and fashion have always been worlds that contaminate each other, especially in stating the image of artists, who become style models for their fans. In recent years luxury has interpreted streetwear in its own way, becoming a mirror of what's happening in the world. In the same way, music does everything it can to get into the world of fashion: the attention is reciprocal, musicians and singers become trendsetters, and the graphics definitely reflect this mixture. If we then talk about packaging, the traditional luxury codes are mirrored in limited editions to give them value through hot stamping, the choice of substrates and refined paper solutions. Hot stamping requires high print runs, but it is also found in limited editions to give added value to collector's series.

What about sustainability?

A record is a product that is meant to last, which becomes part of a collection and is often resold: the second-hand market is robust, so products often have a second life. But, using sustainable materials is a choice that sends a powerful message from the artists, and in the case of those who have a large audience it has a substantial social impact: I'll use the example of Jovanotti, who chose to use only recycled plastics for the Beach Jova Party. Personally, I believe that the creation of a product is always the result of a balance: I've always tended to prefer natural papers, I don't like plasticization even though I'm aware of its protective function, and I don't particularly like packs containing plastic, but customers often ask for them. Being able to lead them towards sustainability is a conscious effort, and you can get excellent results as long as you can enter into a logic of advantageous production costs.

PAOLO PROSERPIO Born in Milan in 1977, in 1989 he saw "Back to the Future, Part 2" with the central character, Marty McFly, travelling on a skateboard. That's where his passion for art, music and painting began, encouraged and stimulated by a very creative and open family. After three years at the Academy of Architecture in Mendrisio, in 2002 he graduated in Graphic Design at IED (Istituto Europeo di Design) in Milan. During his studies, he worked for three months in Gucci's London Graphic Design office and, as soon as he graduated, he started working for Versace. This collaboration continues to this day. For eight years Paolo Proserpio has been the owner of a graphic design studio focused on graphic design/art direction of products that are mainly printed: corporate identity, give-aways, packaging, T-shirts and record covers. Versace, Pinbowl Skatepark, K7 Records, Paula Cademartori, Maggioni Type, Punk Rock Raduno and various groups from the Italian and international underground scene are the studio's leading clients. Always passionate about screen printing, the basis of DIY production/culture, he has participated in several courses related to this discipline at St. Martin's School of Art and East London Printmakers (London). Since 2005 he has been working as a lecturer at IED in Milan, taking care of the "Brand Design" and "Printmaking Techniques" courses; he also holds two workshops a year on screen printing at the Domus Academy (Naba). Probably because of this passion for materiality and printing, until now he has never believed much in social networks and thinks that the best way to promote himself is to try to do a great job.