PepsiCo's recipe for innovation

Design as a creation of meaning and value for society. Diversity as a responsibility and a prerequisite for innovation. Mauro Porcini is the first Chief Design Officer in the history of PepsiCo. He joined the American multinational eight years ago to instil a new design culture on a global level in all its versions. It is present in over 200 countries around the world with a portfolio of products that includes, in addition to the iconic soft-drink Pepsi, brands such as Gatorade, Lay’s, Lipton Ice Tea, Quaker, Tropicana and Looza, just to mention those in Italy. To achieve this, he created a structure - the PepsiCo Design & Innovation Centre - which branches out from New York to 12 other locations in the U.S. and around the world, and leads a team of 270 people. We asked Mauro to share with us his vision and PepsiCo’s strategies in the current moment full of changes, challenges, and, why not, new opportunities.

By Michela Pibiri | On PRINTlovers #83 | Italian version

Some people say that the long period of isolation that has affected us recently has brought down every psychological barrier between digital and human. Meeting Mauro Porcini like this, in a video call in the New York time zone, is an event that properly restores the sense of a naturally lived hybrid community that until a few months ago had been unthinkable. The exceptional event is for having a detailed look at the strategies that PepsiCo - leading multinational in the global food & beverage sector with 2019 revenues of over $67 billion - is putting in place at a time of global crisis and considerable social unrest such as this. Strategies in which design plays an essential role in the management of a truly vast geographic and product portfolio.

What is the role of design today in a global company that addresses very different audiences from a geographical and cultural point of view?

The designer is, by definition, a professional who spends his or her day as an ethnographer, anthropologist and psychologist, trying to understand people’s needs and dreams to create solutions that have value for them. They might be products, for those who do product design, or brands, forms of communication, packaging or experiences. There are those who design the products and brands of today, and there are those who try to imagine those of the future, and this is what we do in our Design & Innovation centre. In our work, we always have to take into account three pillars. The first is the human sciences - the so-called desirability: designers come to the human being from a point of view balanced between emotions and rationality to create something that people love, whether it is defined as “cool”, or “meaningful”. The second pillar is viability: creating economic value for the company. This is an essential aspect even for the purist designer, who wants to create value for society regardless of economic value: an approach, if you like, that’s a bit idealistic and common to many young designers. To them, my answer is that creating financially relevant products is necessary to create value for the company. We must rely on a business and distribution network that can reach as many people as possible with our ideas. The third pillar is feasibility. This is the moment the idea - rich in meaning and marketable – has to be produced using the manufacturing processes that are right in terms of what the company can do. Even the most amazing ideas have to take into account technical constraints and what can be achieved with the right profitability. Everything, for us, must balance between these three dimensions.

What are the main changes, in terms of approaches and innovations, that are taking place in the field of large-scale design?

We live in a world where today more than ever, it is necessary to focus on people. In the history of global business, the human being has never really been at the centre, except in the initial stages of invention and putting brands and products on the market; but the moment people began to think on scale, within those same successful and hyper-efficient companies, that initial human value was often lost. Innovation, once the prerogative of large companies that had a monopoly, was all about business, but things are radically changing because anyone can now have access to finance thanks to crowdfunding or entities of various kinds that support start-ups’ ideas. As well as that, the cost of technology is going down. You just need to think of digital printing and 3D printing that allow you to create products in short runs at reasonable costs; e-commerce enables you to get directly to the consumer, social media allow you to communicate. Technology, communication, distribution: these are all areas that once represented insurmountable entry barriers, and prevented competition with large multinationals and their billion-dollar budgets. Looking at this new landscape of start-ups, if a multinational doesn’t create something of value for the human being, something relevant and exceptional, it has to be aware that someone else will do it instead. They just need to be weak in one dimension - from the product to the communication, from the packaging to the distribution up to the purchasing experience - because the new realities attack the multinationals’ business starting from needs that haven’t been met. Large companies no longer have the chance to protect mediocrity through entry barriers: excellence will win.

PepsiCo has put diversity at the heart of its corporate philosophy. How did you come to this real revolution of values, and what do you do concretely to overcome social inequities?

In the United States, there is a mighty egalitarian push from society. We’re seeing it these days, but it is a need that goes way back in time and the issues of diversity in large multinationals are the order of the day. We have a Chief Diversity Officer, but all the big companies are making the same conscious effort to some extent. Indra Nooyi, our former CEO (from 2006 to 2018, ed), was undoubtedly an icon of this evolution. Her professional profile grew within the company, and her position was chosen in the board of top managers to demonstrate an approach that the company strongly desired and that she carried forward in an even broader and more balanced way. I personally push in the direction of diversity for two underlying reasons. The first one is that companies like PepsiCo, with their vast resources, visibility and access to billions of people, have a social responsibility to help communities that have been discriminated against, marginalized or exploited throughout human history and still are. To show that with some figures, in PepsiCo we have 43% women and 57% men, but we still need to make an effort to balance the team equally. We have the biggest recruiters in the world but, especially in design it’s still difficult to find women and people of colour in high-level roles, and the reasons are social: the types of studies taken, socio-economic constraints that lead to career breaks. We have to force the search for these talents, even if statistically there are fewer of them, to get the right representation in our mix and to send a clear message to society that the conditions that create inequality at the outset are also changing. The second reason is that to innovate, we need to observe the reality surrounding us with fresh eyes, those of Pascoli’s “little boy” who keeps the ability to marvel at every detail. I apply my point of view, but if I have someone next to me with a different cultural background because he or she comes from another country, is of another sex, has other political, religious and sexual preferences - obviously, we’re reasoning by macro-categories that don’t cover the full complexity of the issues - then diversity is no longer just a social commitment. Those individual points of view different to mine represent millions of people. All together, they potentially represent the whole of humanity. Diversity is the possibility of creating innovation where no one had ever seen an opportunity.

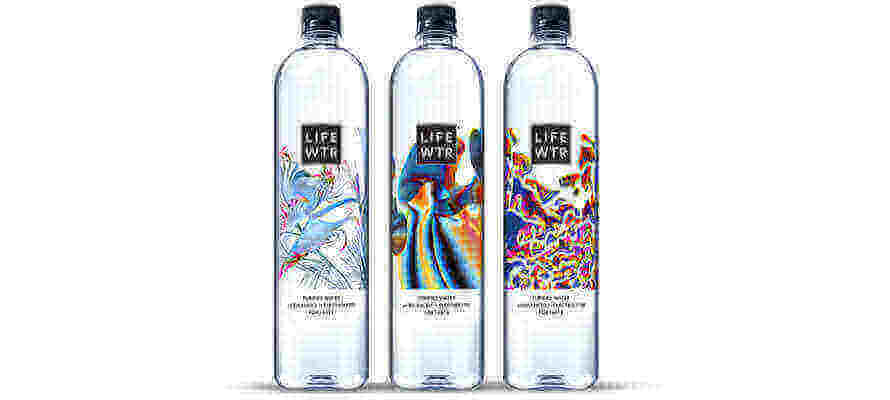

How is it possible to convey the values of inclusion and emancipation through packaging? I’m referring to a brand like Life WTR, which supports communities of artists and is part of the great debate about the low presence of female artists in American museums, or Stacy’s, which supports the ideas of female entrepreneurs.

There are three levels of interaction between people and products. When they are in front of the shelf, or in front of a monitor, people are attracted first of all by what they see, in a visceral interaction where the aesthetics of the product are fundamental. Then comes the moment when you interact with the product from both a rational and emotional point of view: you take it in your hand to understand what it is and if you really want it. The third moment implies a reflective relationship, and it is triggered when that product actually makes sense to the consumer, who wants to talk about it to the world because it stimulates and inspires him or her: we call it semiotic benefit. As designers, if we’re going to move forward with inclusion, we have to, first of all, create a product that triggers a visceral reaction, has a strong impact and creates emotions: all the talk about diversity comes after - as in the case of Life WTR - the investments we make to support creative communities emerge when knowledge of the brand becomes deeper. The aesthetic part of the design, which blocks people in front of the shelf, is the vehicle to trigger the dialogue.

Let’s go back to feasibility. What is the role of printing technologies in your creative process?

Technologies are critical in trying to create the impact I’m talking about. On the Life WTR label we have used printing technologies that work on different layers to give more depth to the graphics and more impact to the extremely bright colours. Such sophisticated graphics help us to place that bottle on a premium level: we’re talking about art, so paying extreme attention to print details is essential. On the other hand, there are technological limitations that prevent us from doing to scale everything we imagine for our brands. My dream would be to be able to flexibly print different graphics for different brands very quickly, so we could react instantly to trends and what is happening with total packaging flexibility. These are possibilities that digital printing provides, but they don’t apply to the immense volumes of production – we’re talking about billions of pieces a day - that we have to support, both for a question of cost and for production speed. We do use digital printing - even direct bottle printing - in our laboratories, but limited to micro-editions. I dream of a total integration between the packaging structure and the labels, the possibility of working on extreme transparencies without defects - bubbles, detachments, scratches - so that the brand and the message totally fuse with the shape of the bottle and the can, all at affordable costs for the consumer. PepsiCo invests billions of dollars in technological research and development: printing is an issue that we are examining from every possible angle because - apart from the creative and innovation demands - for us, with the volumes we produce, the slightest modification to an ink or in grammage has a huge economic impact. But I, being a great optimist, think of limits as an opportunity: I can’t wait for someone in the technical and scientific world to solve a problem to allow designers and companies to innovate. On the other hand, even today, in Italian design, the enlightened entrepreneur or creative is still celebrated, but everyone always forgets the third crucial figure - the technologist, the scientist, the one who takes the dreams of two crazy visionaries and turns them into reality. Without him or her, nothing would happen: visionaries spend hours and hours in the factory with the craftsperson, the scientist, the engineer to solve the problems of manufacturability.

Where are we with the sustainability of the supply chain in the eyes of consumers, and what is PepsiCo’s approach to the need for a global ecological transition?

We need to educate seriously about sustainability, with school and the media as starting points, to avoid shallow approaches. Let’s take plastic: from a simplistic point of view, it’s an obvious problem, because we find it spread over the environment and it kills life forms. But if you look at the entire production cycle, you find that aluminium and glass often have a much higher impact than the broad category of plastics. The first key concept then is to observe the entire life cycle of the product, from production to transport and distribution to use and disuse. We have to remember that the only zero impact product is the non-product, but since we need products and we can’t be idealistic in the extreme, the second concept is reuse, and the third is recycling. But these two steps have implications outside the company, from the consumer to the governments that have to provide the necessary infrastructure. Our strategy involves working on all three of these dimensions, which is why we’re part of several consortia together with other multinationals, including our competitors. Once we’ve done our bit, the fundamental element is the collaboration of consumers who can change their habits starting from closed ecosystems, such as work environments. In our Design Centre, for example, except for Life WTR which has the rPET bottle, there are no plastic bottles. We acquired SodaStream a year and a half ago because for us, the future is in the reusable container, yet it is still struggling to establish itself among consumers.

Crisis and opportunity related to Covid-19. Do you think something has changed irreversibly? What is your vision for the approaches and innovations that will be needed in the near future?

The Covid-19 crisis is accelerating a process that was already underway. This sense of general empathy, of calling priorities into question, the awareness that we are guests on this planet and that nature can get rid of us all in an instant is bringing out what is critical. Personally, I’m convinced that we’ll soon be back to normal, and I need to understand what this crisis can generate that has value in the long term. First of all, digitalization. We were already studying interaction with touchless vending machines, connected to the phone to give commands and authorize digital payments. But there are a lot of areas of design innovation that this virus may speed up, also from a hybrid life point of view. You need to be careful though with the types of design that won’t make any sense in a year or two, like redesigning restaurants and shops to allow social distancing: dividing panels, face-coverings, lack of interaction are not the “new normal”, but the “temporary normal”. The real innovations we have to focus on are those that are sustainable over time. The most worrying aspect, however, is that in the face of a new sensibility, as soon as we’re out of the crisis, we’ll return by default to certain habits of “before”. I’m referring to the extreme rhythms of life, the fact that we put work before our happiness. Unless leaders - I’m talking about the world of business, politics, entertainment - take strong positions, as Giorgio Armani has done in the fashion industry, and chart a different direction, also showing the economic and productive benefits of new work models that put human happiness at the centre of everything.

Mauro Porcini

Mauro Porcini

Mauro Porcini was born in Varese in 1975 and studied at the Politecnico di Milano. He joined PepsiCo in 2012 as the first Chief Design Officer in the history of the American multinational. His mission is to infuse new design culture within the company on a global level, designing innovation and design strategies for current and future product platforms and the corporation’s vast portfolio of brands, including Pepsi, Lay’s, Mountain Dew, Gatorade, Tropicana, Doritos, Lifewtr, bubly, Aquafina, Cheetos, Quaker, Mirinda, SunChips, among others. His responsibility extends to all physical and virtual expressions of the brands, including product, packaging, advertising, events, fashion and art collaborations, retail, architecture and digital activation. The organization created by Mauro for PepsiCo has offices in every region of the world: New York City, Purchase, Dallas, Chicago, Miami, London, Dublin, Moscow, Cairo, New Delhi, Shanghai, Mexico City, Sao Paulo. Before joining PepsiCo, Mauro held the position of Chief Design Officer in the multinational 3M, Minnesota, in a position created specifically for him, where his mission was to build and facilitate a culture of design-driven innovation in a company historically founded on pure technological innovation. He began his professional career in Philips Design and then created his own design agency, Wisemad SrL, together with music producer Claudio Cecchetto. Over the years, Mauro has filed 46 patents in his name and has received numerous design and innovation awards. In 2019 the President of Italy, Sergio Mattarella, awarded him the title of Cavaliere (“Knight”). Mauro sits on the Board of Directors of the Design Management Institute in Boston, on the Board of Directors of the Italy-America Chamber of Commerce, on the Board of Directors of the School of Italy in New York and on various other Advisory Councils of design and art institutions. He’s currently living in New York City.